What the Flock?!

In 2024, Fresno entered into a three-year, $1.6 million contract with Flock Group Inc. Here is what we have learned (so far) about the AI-enabled cameras that have been installed throughout our city.

Since 2020, Olive Avenue in Fresno's Tower District has gotten some (overdue) upgrades. LEDs string overhead, vines of warm light over night life. Local artist commissioned mosaic trash can covers perforate the street. And nested on light poles in front of La Panaderia Natalie and near Neighborhood Thrift are small, unassuming, and easy to miss solar powered cameras, part of a growing surveillance network operated by Flock Safety, a private firm that sells video surveillance products, gunfire locator systems, and “Automatic License Plate Readers” (ALPRs), popularly referred to as "Flock cameras".

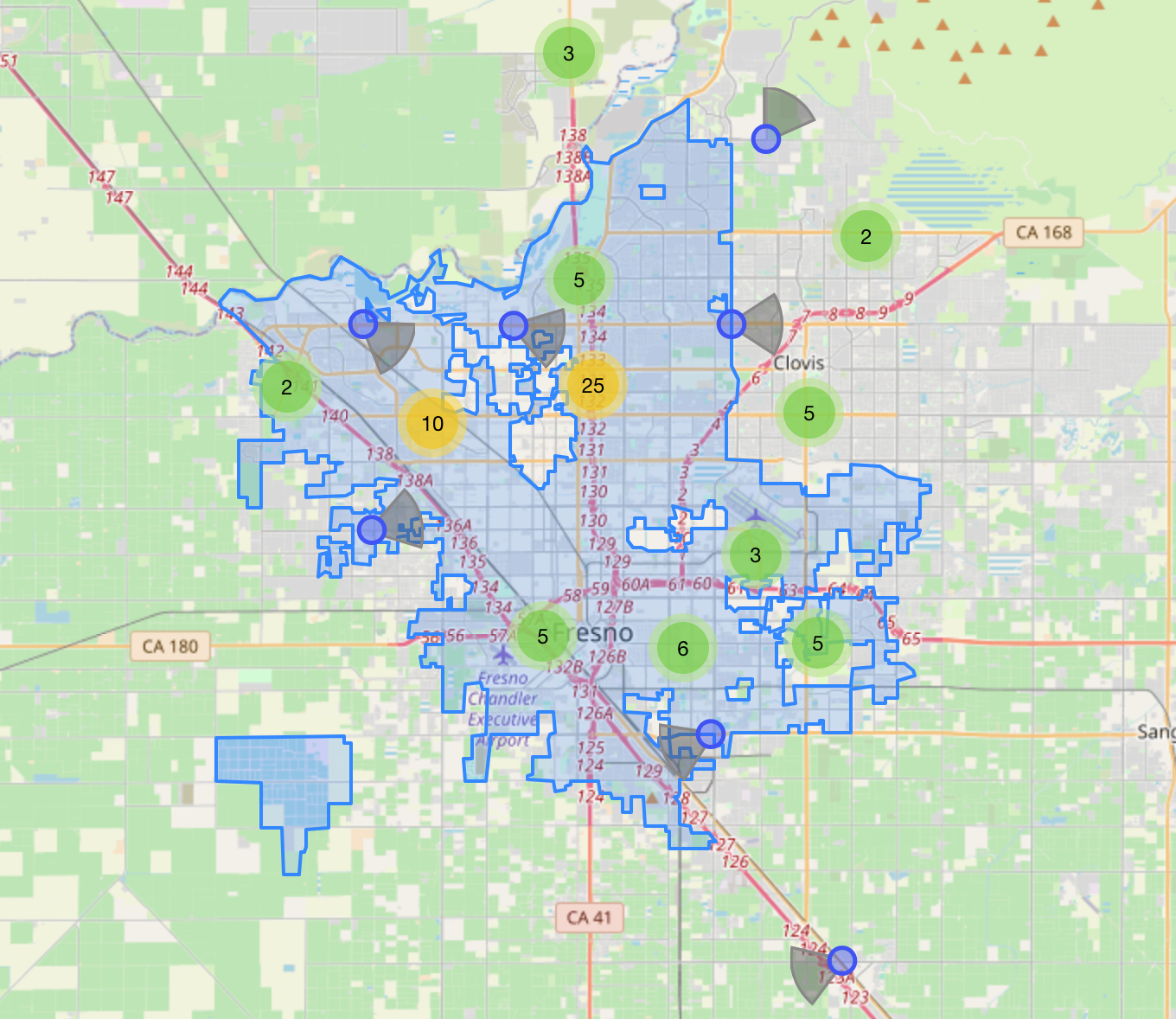

In 2024, Fresno entered into a three-year, $1.6 million contract with Flock Group Inc. According to the Fresno Police Department, there are 70 cameras throughout the city. While Flock, law enforcement, and government officials claim the cameras are for public safety, activists and civil liberties advocates argue they are a quiet expansion of mass surveillance with little public oversight, significant privacy risks, and a growing track record of abuse.

But... aren't they just license plate readers?

Short answer-no. Variations of License Plate Readers (LPRs) date back to the late 1970s and have been used by police since the 1980s. So why the renewed uproar?

We talked to Austin Reilly, a local techy and one of the activists behind the new coalition, Flock Outta Fresno, to help distinguish technological characteristics between the new ALPRs and their predecessors.

"With a license plate reader (LPR), the only data that was being kept somewhere is the license plate. The biggest difference between an LPR and an ALPR is that they're able to process details in the picture ahead of time. So there's already a database that knows that I'm driving a blue car with an 'I hate cops' bumper sticker before anybody searches for that. It's data that's being kept somewhere."

He explained how early systems relied on basic optical character recognition software. Simply put, they scanned images for letters and numbers, captured a photo when a plate was detected, and stored that information for later review.

The new systems are powered by AI and machine learning. So, instead of looking only for license plate numbers, Flock cameras analyze entire images. They can identify vehicle color, make, model, roof racks, decals, your ACAB bumper sticker, and any other distinguishing features including people. They run continuously, capturing and processing data every time a car passes by.

"They may tell us that it's a license plate reader and yet whenever it reads the license plate, it's going to save a picture of your car with you in it." Austin, Flock Outta Fresno

Another significant shift from older LPRs to modern ALPRs is how the data can be searched. The older systems were limited. An officer needed a license plate number first, typically one connected to an Amber Alert or a stolen vehicle report. The technology was reactive, narrow in scope, and far more labor-intensive.

The Flock Safety database operates very differently.

With AI-enabled ALPRs, authorities can start with a description instead. Reilly shared an example where a subscriber looks up "blue Jeep, roof rack". The system then searches across millions of stored images to find vehicles that match. Any Flock camera connected to the system will respond if it saw a blue jeep with a roof rack.

This capability requires enormous amounts of data to be analyzed and stored in advance. In other words, the system must already “know” what it has seen in order to answer those descriptive queries. That means everyone, every commute school drop-off, medical visit, or trip to a protest is logged and becomes a data point.

"I pick my location, it narrows it down and tells me exactly where that Jeep has gone. The reality in that case is that it already knew that, right? So in order for me to query for that means that that data was already present. So before, the only data that was present was a license plate and a picture. Now it's a picture, a license plate, shape, color, who's in it. I mean, it could be anything..."

In short, the Flock cameras are monitoring everybody instead of just targeting specific vehicles connected to crimes, collecting data, and the information is then saved and stored "just in case."

Who Can See This Data?

Reilly points out the ethical problem of surveillance and power, citing the Dark Knight, one of many productions that have highlighted the issue.

In Batman: The Dark Knight, Lucius Fox warns Batman against using mass surveillance to track the Joker.

In the movie, Batman is able to access every cell phone camera in the city and use them to track the Joker. He argues that he "needs to find him."

"Should anybody be allowed that much power to be able to surveil the entire city and see if anything is wrong? I mean, it's pretty dystopian..." Reilly shares, echoing Lucius Fox, Batman's partner, who insists that this is fundamentally wrong even when used for the "greater good." The problem with the greater good is that it is subjective. So who can see the data?

One of the most alarming aspects of the Flock system is that anyone who subscribes to Flock can access the database.

Flock Safety markets its platform to police departments as well as homeowners associations (HOAs), and businesses. Anyone who subscribes and is granted credentials can access the system.

Flock claims to not share data with any federal agencies. However, subscribers have been confirmed to engage in data sharing, or "piggy backing" between agencies further expanding the reach of these cameras from city to state to federal.

For immigrant communities, activists, and others already subject to heightened scrutiny, this kind of surveillance and data sharing has already had direct impact.

Since these powerful surveillance tools have been placed into the hands of people with very little regulations or oversight, several instances of abuse have been documented. To name a few:

- In 2023, a former police Lieutenant in Kechi, Kansas used the cameras to stalk his wife. In 2024 a police chief in the same county used Flock license plate readers to stalk his ex-girlfriend and new boyfriend more than 200 times over several months. They were each sentenced to 18 months probation.

- In Texas, officers used ALPR data to access 83,000 cameras nationwide to help track a woman who self-managed an abortion. Officers say the family was concerned for her safety.

- It's been confirmed that officers have shared data with ICE in Oregon and California.

- Across the country, officers have used Flock cameras to monitor No Kings Protests.

Security Risks and Data Leaks

Beyond ethical concerns, there are serious questions about security. You Tuber Benn Jordan demonstrated that Flock cameras and systems are alarmingly easy to access and how quickly unauthorized users can reach camera feeds.

Benn Jordan shares how easy it is to access flock cameras.

Centralized databases of location data are valuable targets for hackers. When breaches occur, there is no way to undo the exposure of someone’s movement history. Unlike a credit card number, you cannot cancel where you were last week.

Critics argue that entering contracts for widespread surveillance while security concerns remain unresolved is at best deeply irresponsible and at worst reckless.

Constitutional Questions and Legal Gray Areas

AI enabled ALPRs are a legal gray area, a new frontier where companies are pushing boundaries–and community and organizations are pushing back.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) has warned that Flock’s business model effectively creates a sprawling surveillance network that far exceeds traditional policing boundaries. The rapid spread of ALPRs has outpaced regulation. There are no comprehensive laws governing how long data can be retained, how AI analysis can be used, or how information may be shared across jurisdictions.

Legal scholars and advocacy groups have raised Fourth Amendment concerns,

questioning whether constant, unwarranted tracking of people’s movements constitutes an unreasonable search.

“The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.” -4th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

Existing driver privacy laws were written long before AI-powered mass surveillance became possible and are being leveraged by some advocates to regulate the ALPRs.

Surveillance and Marginalized Communities

Surveillance in the United States has never been evenly distributed. Historically, new monitoring technologies are deployed first and most aggressively in communities of color, low-income neighborhoods, and areas with high immigrant populations.

Fresno is no exception. While officials frame ALPRs as neutral tools for public safety, critics note that “safety” often becomes a justification for over-policing the same communities that already face disproportionate harm.

When people know their movements are being tracked, they change how they live, where they go, and whether they feel safe exercising their rights.

Get the Flock Outta Fresno

Fresno is one of countless cities across the nation that are calling out Flock. Cities including Cambridge, Massachusetts; Eugene, Oregon; Charlottesville, Virginia have successfully ended their contracts with the company after community push back. On January 12th, Santa Cruz council members ended their contract, citing Flock's repeated failures, lack of transparency, and unresolved privacy concerns.

“Flock has made too many mistakes and Flock’s leadership has too often dismissed real, valid concern instead of responding with transparency and accountability,” Susie O’Hara, Santa Cruz council member said before voting to end the City’s contract. They were the first in California to do so.

Fresno has been using ALPR systems since at least 2016, previously contracting with Vigilant Solutions, and in 2020, the city failed a state audit. Among the issues described in the audit were privacy & policy deficiencies, data retention issues, data sharing without adequate justification, and insufficient monitoring and oversight.

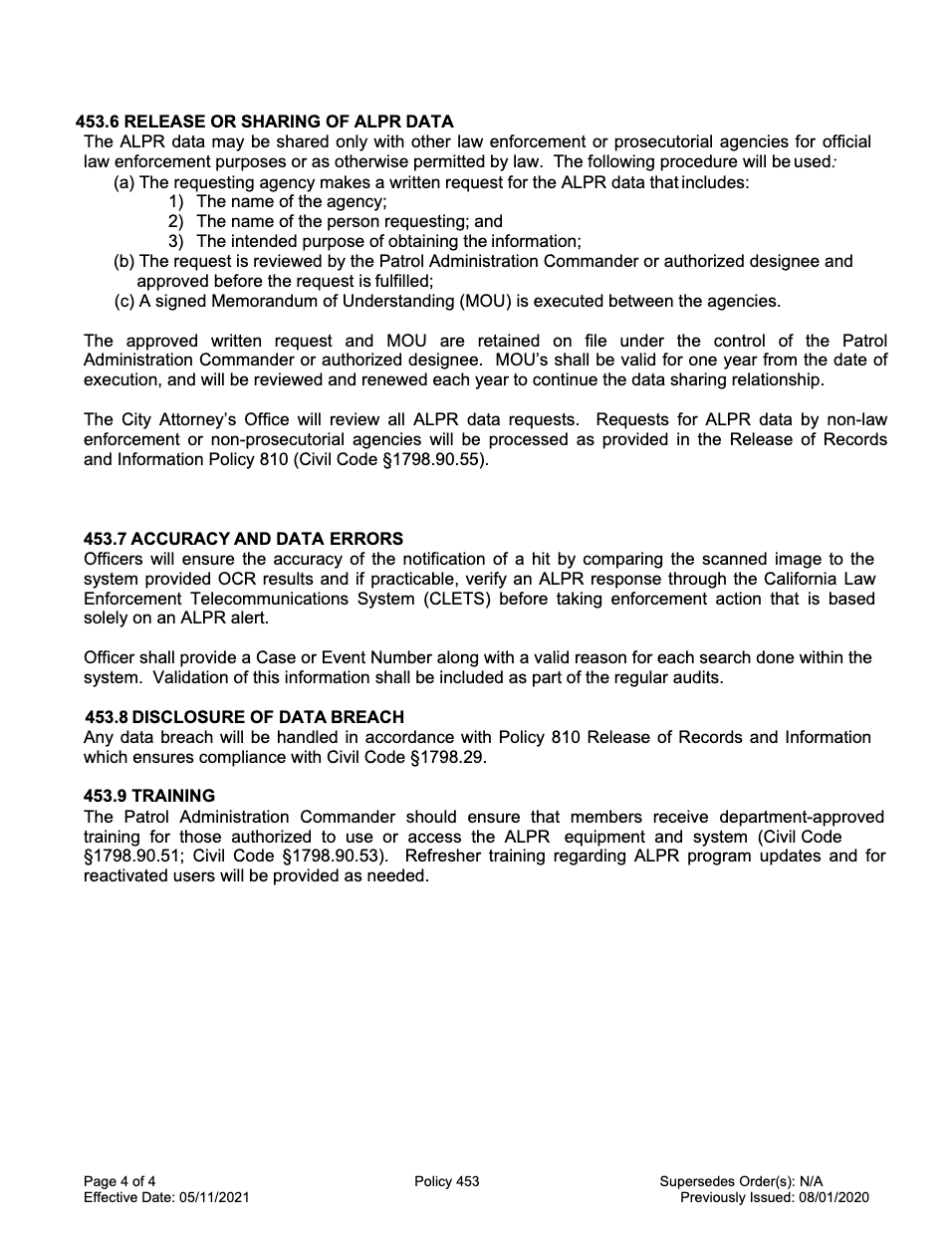

The Fresno Police Department responded to the failed audit with Policy 453 for Automated License Plate Readers (ALPRs) in May of 2021.

According the the Fresno city ALPR policy manual, probable cause is not needed to use the system, data sharing with other agencies is permitted upon request and approval, and all data captured need be stored for at least one year.

There has not been an audit since 2019 to confirm that the policies are being upheld. At the time of publication, records requests we submitted to the City of Fresno and the Fresno Police Department regarding the scope, use, and safeguards of the Flock system remain unanswered.

What the flock can we do about it?

Here are some things you can do as events continue to unfold:

- Stay informed- Follow FlockOuttaFresno for the group's immediate updates.

- If you want to nerd out and do your own research, here is a list of further reading and resources we used in this article.

- Make a public statement at an upcoming city council meeting during "off-agenda" time.

- Email your city council rep using this template.

- Anytime you see a flock camera, add it to deflock.me and/or post or send to FlockOuttaFresno

For activists, the issue is about allowing our communities a say before being placed under constant watch. Consider whether “public safety” should come at the cost of privacy, autonomy, and trust.

"You look at it from a purely like, 'Oh, we can make sure that everybody's safe aspect and it sounds pretty and neat on paper, but I mean, even in the movies they depict how it is a moral problem. You're not supposed to be able to watch everybody," Reilly reflected.

This is a developing story.